Victor Robert Lee's 2013 essay on Beijing's territorial grab in the South China Sea

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSIOn

The world’s last remaining empire is expanding. More than fifty years after the European, Japanese, and American colonial powers largely abandoned their holds on far-flung territories, and more than twenty years after the Soviet collapse, one colonial power remains: China. To its portfolio of Tibet, Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia, Beijing has now added the near-entirety of the South China Sea. Why? Because it can. How? By simply announcing it.

The U.S. and the nations bordering the South China Sea are simply too hobbled or militarily weak to stand up to China’s bald territory grab.

The Obama administration appears, in public at least, not to hear the announcement, continuing to refer instead to amorphous needs for freedom of navigation and codes of conduct. But here is the crystalline statement by China’s Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi in early September: “China has sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters.”

If that isn’t clear enough, an earlier statement by China’s state news agency Xinhua in July was more precise; a newly announced Chinese prefecture called Sansha, the Chinese name for one of the Paracel Islands, will administer “2 million square kilometers of water” in addition to the hundreds of islets and shoals within the sea. That adds up to an expanse almost equal to the Mediterranean.

From The New York Times, April 18, 1939, front page. Beijing’s annexation of the South China Sea echoes Japan’s expansion immediately prior to WWII.

It is no longer possible to pretend that this annexation is something nuanced or limited, especially in light of China’s recent printing of passports that include a map showing the South China Sea as belonging to China, and the recent announcement by the foreign affairs office of China’s Hainan Province that Chinese ships would be allowed to search and deny transit to foreign vessels if they were engaged in any “illegal activities” within the 12-nautical-mile zone surrounding any of the hundreds of islands claimed by China.

How could the “peaceful rise” of an inwardly focused China possibly lead to strident hegemony over other territories? For decades, Western Sinologists and China’s communist party leaders have framed the middle kingdom as a self-centered entity, never on the hunt for foreign properties. If you lived in Boston or Berkeley, the argument was more credible than if you lived in Lhasa, Kashgar or Hohhot (or Vietnam in 1979, when Chinese forces invaded). Beijing’s latest imperial move will bury the illusion of a self-occupied benevolence.

The Chinese Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army-Navy have been biding their time for this moment. The South China Sea has long been a backwater of unresolved borders, disputed exclusive economic zones, and competing claims on fishing and petroleum rights. In addition to China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Brunei all have long-standing overlapping claims. Why is it not still a sleepy backwater?

Two reasons: The muscling-up of China’s navy, and America’s epic military diversion to Iraq and Afghanistan.

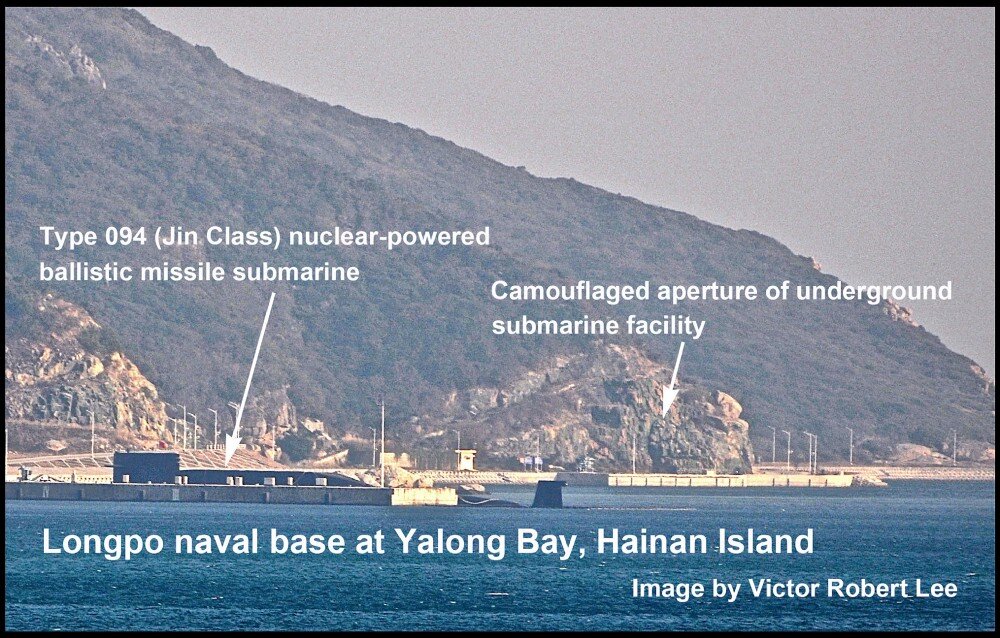

Despite its history of having a mostly ground-based military with marine capabilities limited to its shores, over the past twenty years China has built a major naval force with “blue water” reach, anchored by substantial submarine bases at Ningbo, Qingdao (which U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta visited in September) and Yalong Bay Hainan, the latter two bases having underground sub facilities. The assortment of submarines is complemented by 13 destroyers and 65 frigates, as well as precision-guided ballistic and cruise missiles that the U.S. worries could disable its aircraft carriers and bases in the region. Measured against these advanced weapons, China’s recently launched relic of a small aircraft carrier, the Varyag (renamed Liaoning), is primarily symbolic.

China’s newly expressed territorial ambitions find support beyond the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, extending well into the national psyche. The CEO of China’s state-controlled oil company CNOOC announced in August, vis-à-vis the South China Sea, that “deep-water [oil] rigs are our mobile national territory and a strategic weapon.”

In recent weeks the South China Sea story has been overshadowed by heated frictions between China and Japan regarding the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in the East China Sea. In this dispute China has a claim of ambiguous validity that can be used to harness long-standing anti-Japan and nationalist sentiment, to the benefit of a Chinese Communist Party that must legitimize itself. This tussle provides two other benefits to Beijing—it keeps attention off the South China Sea grab, and provides a robust warning to Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan and the Philippines of the consequences of resisting.

What a difference a decade makes.

China’s neighboring countries on the South China Sea have sailed through the past decade with inadequate defense preparations, lulled by the dissipating notion of a U.S. security umbrella.

The Philippine government’s announcement in August that it is negotiating with Italy to acquire two used Maestrale-class anti-sub cruisers, possibly a year from now, illustrates the feebleness of its maritime position. Two decommissioned coastguard cutters—stripped of weapons—that have been recently transferred from the U.S. to the Philippine Navy are Manila’s most advanced ships.

The Scorpène-class submarine sighted at dock by this correspondent in September at Malaysia’s Sabah naval base still requires French naval personnel to operate properly, according to a well-informed individual in Malaysia. (The country received its first two submarines in 2009-2010, a procurement that is now the subject of a corruption investigation in France.) One of the submarines was deemed unable to submerge by the country’s defense minister shortly after its delivery; the government now claims it can dive.

Belatedly, Vietnam has begun a serious naval rebuilding, deploying in 2011 its first two Gepard-class light frigates. More significantly, in 2009 Vietnam ordered six Russian-built kilo-class submarines, the first of which was launched for initial sea trials four months ago at St. Petersburg. With their stealth capabilities, extended combat range, and weapons for land and sea strikes, these subs will markedly complicate Beijing’s regional naval posture. But deliveries of the vessels are not likely to be completed before 2016, which is all the more reason for an assertive Beijing to make its South China Sea move now.

The nations in the neighborhood are obviously weak compared to Beijing’s forces, so what about the historical protector and stabilizer, the United States? Its draining wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have created a decade-long vacuum in East Asia. Beijing has likely calibrated its latest imperial move to occur just prior to the U.S. military’s final extraction from Afghanistan, after which the U.S. will theoretically have more capabilities to deploy elsewhere.

Now the U.S. is urgently trying to fill in the vacuum with a loudly broadcast “pivot” that so far is more talk than substance. Will it be sufficient to deter Beijing from taking a bite out of mineral-rich Mongolia on its northern border, or colonizing rickety Myanmar to the south, with its hydroelectric potential and Indian Ocean access? These questions are open for consideration only because of the self-injurious actions of the world’s current superpower over the past ten years.

An overused phrase of officials in the administration that launched the U.S. into the bog of Iraq was “Weakness is provocative.” With painful irony, it is the debilitating lost decade in Iraq and Afghanistan that enabled Beijing’s recent nimble territory grab. It is time to see the Beijing Empire for what it is: a hegemon that has been emboldened by America’s folly and is expanding.

* * *

Victor Robert Lee reports from the Asia-Pacific region. His articles on the South China Sea, the East China Sea, China, Indonesia, and other Asian territories can be found in The Diplomat and elsewhere. His reporting has been cited by The Guardian, BBC News, CNN, The Economist, Mainichi Shimbun, The Singapore Straits Times, Asahi Shimbun, Bloomberg View, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Week, National Geographic and other media, and in hearings of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.